Is the real world fading from our lives?

Christine Rosen's Extinction of Experience lays out what we're all feeling but can't quite articulate: life feels a lot less alive than it used to.

I remember sitting cross-legged on a bunk bed in a hostel room, alone, staring into my laptop. It occurred to me that I was a hemisphere away from home, and yet my world hadn’t really changed. I was still logging onto my laptop to do my job, still signing into Facebook to talk to friends, and still streaming reruns of TV shows to numb myself out.

I was doing everything my parents had done at my age: backpacking around the world, looking for answers in new cities and new languages, falling in love and breaking it off. But somehow it felt like my turn was different.

I remember having the terrifying thought, alone on that bunk bed, that one day ‘human society’ might simply refer to individual humans sitting in individual white-box rooms at their individual screens, eating their meals in capsule form and conducting all the business of ‘being human’ through digital displays.

I was twenty.

That feeling — that my real life was something that happened behind a screen — is what Christine Rosen explores in The Extinction of Experience. “Today, many of us choose to live in a form of pseudo-reality governed by algorithmically-enabled individual experiences,” Rosen says in her deeply resonant introduction. “Much of what passes for authentic experience today is vicarious and virtual.”

It’s hard to disagree with this characterisation of modern life. I think millennials might feel this more pointedly than anyone. We’re old enough to remember growing up in a mostly physical world (oh, how we took it for granted), but young enough to have not really been able to experience adulthood this way. We don’t know what it felt like to get your morning news from a newspaper, or spend a cosy evening on the phone to a friend who lives across the country, landline phone tucked between ear and shoulder as you doodle on the Yellow Pages. We don’t remember what it was like to write out recipes from aunties on index cards, to make a mental note to ask someone about something at church next week, or to meet your soulmate at a barbecue.

Scientific and technological progress has generally been a good thing for most people. The Enlightenment brought us, well, the truth; the Industrial Revolution lost a lot of people their jobs but also brought us the middle class; the Internet brought with it the potential to democratize, well, everything. Now, everyone had information, and everyone had a voice. All of these things brought positive change. But we have to acknowledge the destruction that innovation leaves in its wake.

Rosen quotes Ursula Franklin: “It may be wise, when communities are faced with new technological solutions to existing problems, to ask what these techniques may prevent and not only to check what the techniques promise to do.” Likewise, although the digital world has given us much worth celebrating, Rosen maintains (in reference to digital classrooms, but the message applies broadly) “it is worth asking what we are giving up in this new world of [the] virtual.”

This is a question we should ask frequently. What cognitive and navigational skills do we give up when we trade paper maps for blue dots on Google Maps? What quality of conversation do we lose when seeing a friend for dinner after texting them all day? What kind of stupifying brain fog are we learning to live with when we check our phone a hundred times a day? On and on it goes.

The Extinction of Experience covers all of this, and more, in alarming, disconcerting detail. You will nod in recognition throughout — all while wishing you weren’t.

For a deeply personal and introspective book, it is particularly well structured. Rosen’s first chapter is titled “You Had to Be There.” Apparently, the use of this phrase grew in popularity from the 1960s, peaked in 2012 (the year that saw the fastest year-over-year in American smartphone usage), and has been dropping ever since. That’s insane. I remember saying this. A lot! And now? I honestly can’t remember the last time I said or heard it.

This sets the tone for the rest of the book. Rosen moves on to her second chapter: “Facing One Another.” Here, we learn about the social and biological benefits of reading faces and non-verbal cues — and how much emptier our interactions are without them.

The third chapter, “Hand to Mouse,” explores the rapid extinction of handwriting skills among new generations. In losing handwriting, we’re not just losing a beautiful art or pleasurable craft; we’re also missing out on the tangible cognitive benefits that arise from the physical effort of writing words out by hand. Kids are poor spellers, struggling readers, and abysmal hand-writers. They’re also performing worse at other fine motor skills, which is no surprise when many kids are spending their days simply swiping, tapping, and scrolling.

Kids are the real victims of the social media movement. If we can’t muster the motivation to address it for ourselves, we should at least think about what we’re withholding from our children when we are overly forthcoming with digital access.

Chapter four, “How We Wait,” reminds us of a time when we could wait for a bus, a coffee, or even an elevator without feeling that uncomfortable urge to check our phones. In insulating ourselves from the experience of boredom and never needing to waste an unentertained minute ever again, we’ve also destroyed any sense of patience we might once have had. Even a two-second delay loading a website gets us riled up. In forgetting how to do nothing, we are increasingly losing the ability to do anything.

Chapter five, “The Sixth Sense,” explores how “spending a lot of time in mediated environments undermines our ability to read others’ emotions” — and our own. While we’re busy “hearting” Instagram photos and reacting to text messages with crying emojis, we’re losing social skills that make real human interactions enjoyable and meaningful. At the same time, we’re getting angrier and more envious the more we scroll — but increasingly unable to realise it. College kids are scoring 40% lower in empathy than they were 20 or 30 years ago. ‘Social’ media is, ultimately, anti-social.

Chapter six, “Mediated Pleasures,” hit me hard. Here, Rosen dives into the world of twenty-first-century travel: one where accommodation is pre-vetted and booked online, restaurants are carefully evaluated and menus consulted before we set off for lunch, and, most importantly, the very sights we’re there to see are pre-experienced on Instagram and YouTube ahead of time. All of this makes for a travel experience that is highly insulated, almost never truly uncomfortable, and yet almost always a little underwhelming. The colours of the Amazon are a little desaturated compared to the Instagram photos; the streets of Marrakech a little less bustling than they seemed in the YouTube video; the scale of the Grand Canyon seemingly a little smaller than the photo exhibit in National Geographic.

It’s not just a travel problem. The world of algorithms thrives on extremes. The things that make it to the tops of our feeds are the most extreme, hyperlative examples we can hope to see: the most beautiful person, the most muscular gym-goer (who is, by the way, on steroids), the tallest mountain, the bluest water, the cutest baby, the wildest life story. We’re so numb to extremes that we’re basically bored to death of anything that doesn’t measure up. “Reality, by comparison,” says Rosen, “is uninteresting.” She’s right. I feel it even with the little things — board games are an agonising thought these days. Museum signs? Forget it. A nice coastline? Doesn’t look like the Maldives.

Even when we reach the peak moments of our trips — the ones we’ve been dreaming of for years and planning for months — we spend more time capturing the moment to look at when we get home (which we hardly ever do) than we actually do taking it in. Actually, if we’re honest with ourselves, we’re capturing it more for others than we are for ourselves. Here, Rosen tells the story of witnessing a double rainbow in D.C. Immediately, her colleagues whipped out their phones to photograph the experience to share online. But as Rosen laments: “How can you share an experience that you’ve barely paused to have? Were they even having an experience or merely documenting a scene wherein an experience might happen?”

Documenting a scene wherein an experience might happen. I’d say that’s 99% of travel, and moments with friends, and basically anything remotely picturesque these days. Most of the people I see at the top of mountain lookouts or places laden with history barely even step through the arched doors before they’re photographing or filming. They spend almost their whole time taking in the experience through their six-inch screen rather than their full-colour, HD, 360-degree vision.

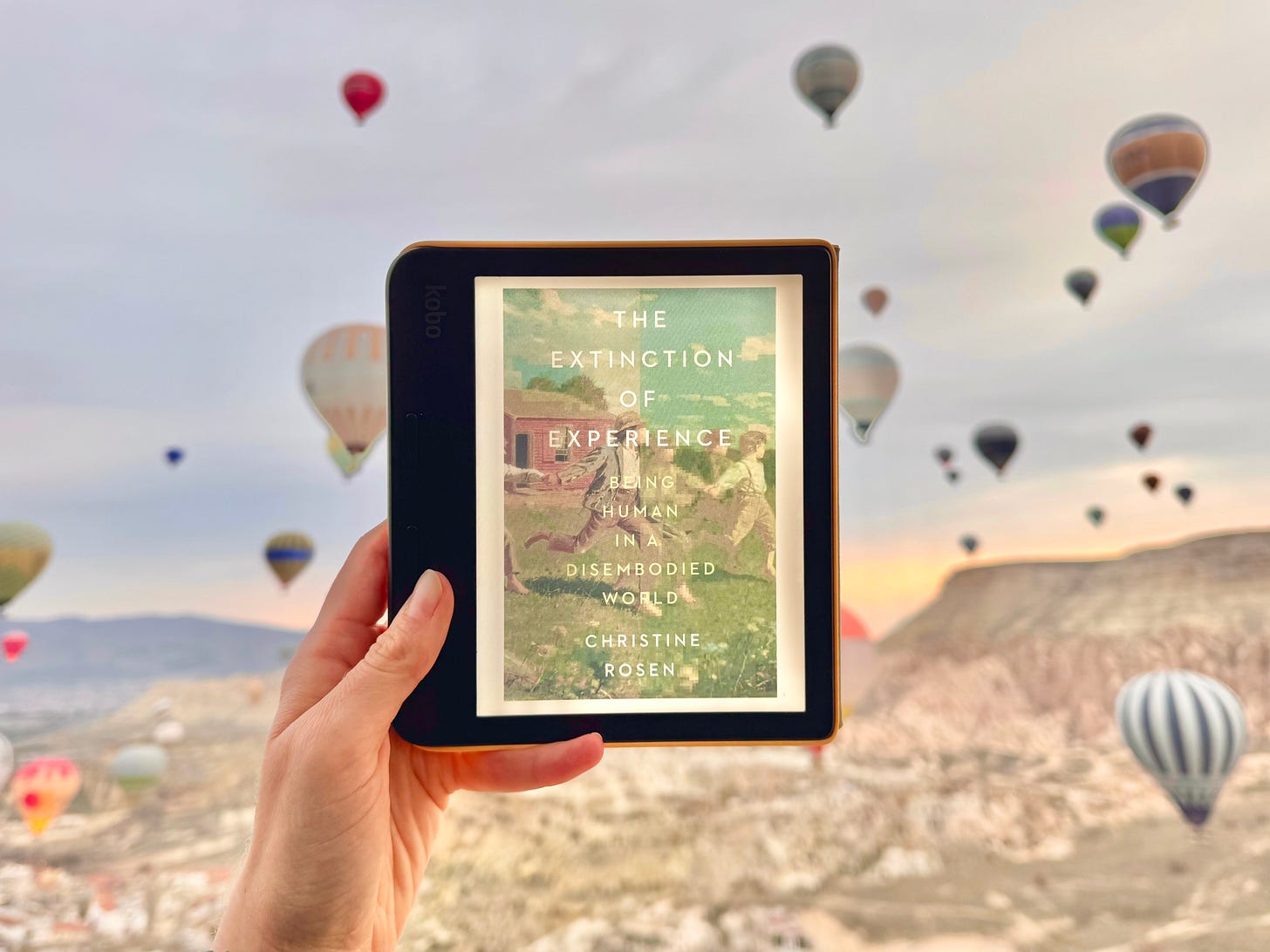

Even though I know this is a problem, I still find myself doing it. Take my 30th birthday hot air balloon ride. I was reading this book at the time, so I was extra conscious to try to simply take in the experience of being in the balloon and not just get the perfect photo. And yet I still spent more time snapping than I did actually seeing. Even while consciously trying to take in the moment, I still couldn’t shake the feeling that I hadn’t snapped the perfect photo yet.

Finally, in chapter seven, Rosen breaks down how the digital world has left a crater-sized hole in our experience of “Place, Space, and Serendipity.” We lament the loss of third places and shared public spaces these days — as we should — but we rarely stop to acknowledge that even if we built more or better spaces, we would still only be half-there. Wherever we go, there our phones are. Now, we can pre-order our coffees online and leave a one-star rating if the place disappoints us, but we’re also much more likely to become lifelong friends with the person at the table next to us.

Previous centuries — even decades — have framed discussions of technology around promise. The next big tech breakthrough will solve this, disrupt this, bring eternal happiness. The 2020s feels different. Technology, which has been screwing with us for a while now, has finally revealed itself as non-neutral: a potential bad guy. I’m glad we’re finally confronting it.

As we confront it as a society, I think we’re seeing glimmers of hope.

At thirty, I’m on another world tour — call it a quest to stamp the empty pages of my passport before midlife throws a different kind of adventure my way. This time around, I’m seeing things I didn’t see ten years ago. For one, there are people with books — quite a few of them. There are kids at dinner tables with sketchbooks and pencils — not an iPad in sight. There was the young couple playing cards at a rooftop bar, the men playing chess in the town square, and hundreds of people carrying around old-school film cameras (my friends included).

Something is happening here. More and more, it seems like people are “sick of how all of this feels” — a phrase I’m positive I heard Ezra Klein say in a podcast recently but can’t find to link here, in reference to how the digital has taken over our lives. Governments, including my own in Australia, are taking the dangers of a digital life seriously. People are dumbifying their phones, pulling out their first phones from storage to see if they work, buying analogue alarm clocks, jailing devices in lockboxes, and picking up new or old hobbies again.

Ads everywhere are encouraging people to “replace scrolling with” whatever alternative they’ve come up with. So many of the non-fiction bestsellers of the last few years have been a response to digital frenzy (Sirens’ Call, The Lost Generation, Stolen Focus, Slow Productivity, to name a few). All over Substack, I see notes like this:

I think the resistance is growing.

The good news is that, as alarming and depressing as this book is, it’s also profoundly motivating. If you’re old enough to remember what life was like before we carried our phones around like oxygen tanks (a particularly striking metaphor from the book), then tapping into that feeling is the place to start. If you’ve grown up with a smartphone in your hand, I imagine it’s going to be harder — but not impossible.

We can take matters into our own hands, but this is also a structural problem. Even if a few radical conscientious objectors reject the digital life, the physical world has already been downgraded. You can go phone-free on the subway, if you like, but good luck chatting to the person next to you. More and more, the physical world is being converted into ones and zeroes. You frequently can’t get what you need in-store (“sorry, it’s only available online!”), can’t get your coursework or talk to the school without it (“it’s all in the portal!”), can’t drop a resume over the counter anymore (“have you applied online?”), can’t buy a ticket at the ticket office or find a human being who can help you (“chat with our AI help bot!”). With every software update, we downgrade the real world. It is not just Black Rhinos and Dodos we’ve driven to extinction. In our attempts to conquer the world, we are beginning to extinguish our very experience of life itself.