Never Let Me Go, by Kazuo Ishiguro

A haunting book about the dark side of progress, the brevity of human life, and the way we surrender to our fates.

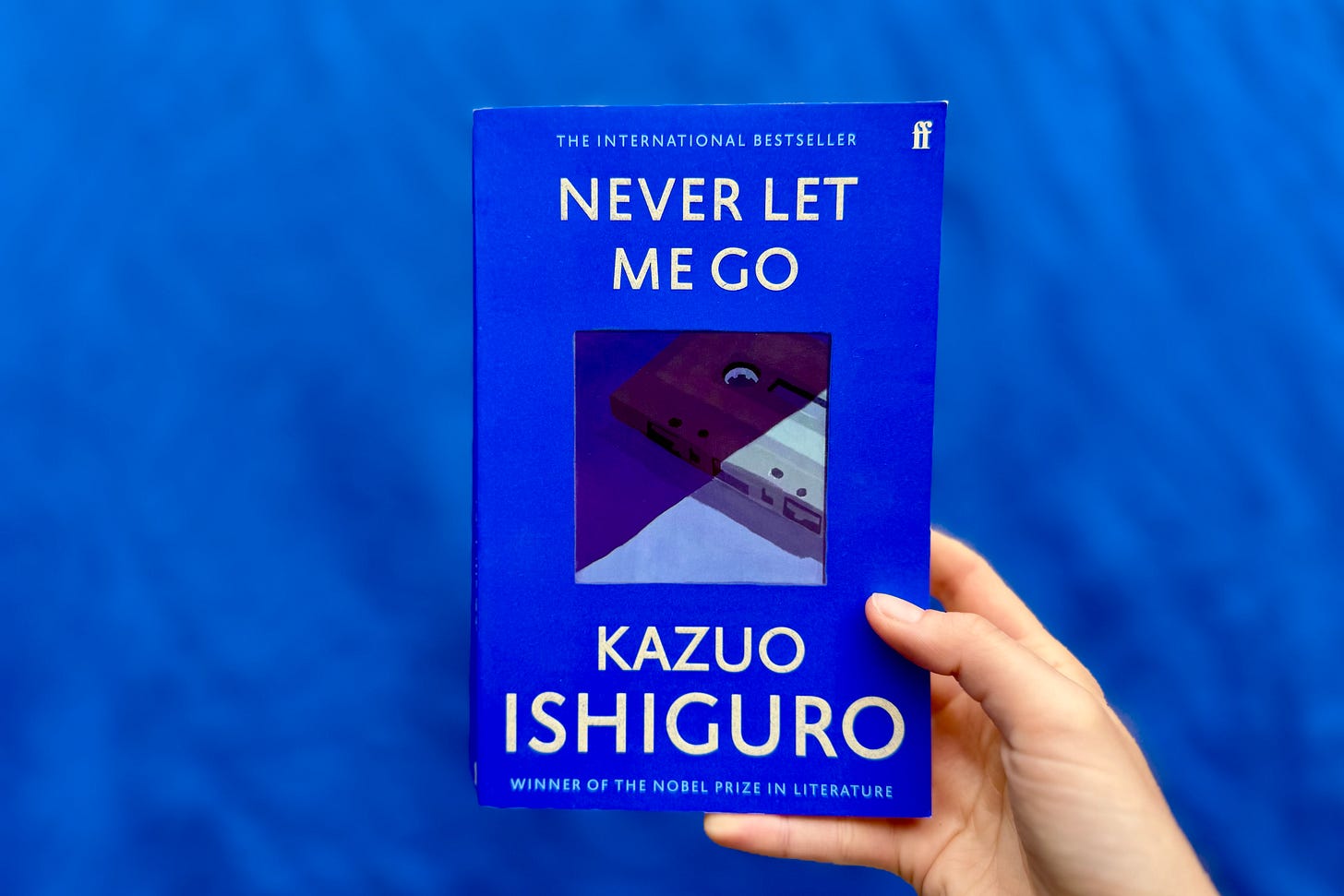

Sometimes I buy books based on colour alone. My copy of Never Let Me Go all but called out to me from a lone stand in a bookstore I had only just discovered in the middle of Brisbane suburbia. The deep ultramarine blue was so captivating that I bought it and took it to the beach with me to read over Christmas.

I had a vague idea of the premise — human clones are raised in an English-style boarding school — but not much else. This is also, as the Bookstagrammers may be horrified to learn, my first Ishiguro book.

Knowing what I did about the clone situation, I opened the book waiting for the moment when the characters decide to rebel — to escape their fates, to slip out of whatever system was holding them captive.

But a natural consequence of following the characters on their journey is the realisation that the ties that bind these people to their world and their fate are not physical but psychological. This becomes particularly obvious when they move into the ‘Cottages’ and have the ability — even access to a car at some points — to go wherever they wish. Yet over the course of a year (don’t quote me on that) at the Cottages, the characters venture out only once (for a particularly uneventful day in town). It was only when I imagined these characters existing in a public space with other people that I realised just how shy, sheltered, scared, and almost *not-*human they are as a result of the extreme isolation of their upbringing.

But while these characters are certainly unusual when contrast against ‘normal’ people, the way Ishiguro chronicles their experience is not about the unusualness of being a clone about the very ordinariness of human mortality. The way the donors sit around at the medical centres in semi-circles of chairs, or are tended to by their carers, is really just a snapshot of old age, acted out by the 20- and 30-year-old bodies of these particular characters. But life is short no matter how long you get. Aging is painful and isolating, whether brought forward by circumstance or occurring naturally via the passage of time.

The dark underside of the world this novel builds remains a relevant social critique today. We get glimpses of what the ‘other’ world is like — the world in the same country where people are thriving in a world free of cancer and other suffering, but the tradeoff is the point. The underworld fuels the shiny happy world, much as today’s sweatshops, Amazon factories, factory farms, and so on, have become the misery that fuels our purchasable happiness.

Every element of this book, for me, added up to a heavy feeling of inevitability, of coming to terms with what lies ahead, such that in the end, it was no surprise that there were no grand escape plans. Not escaping is the point. I still wondered about this, though, even after I had finished the book. What, technically, was stopping them?

I Googled it, and sure enough, found plenty of people asking the same question. The director of the movie adaptation had spoken about this at length thanks to the incessant asking by audiences.

“Maybe it’s a failing of the film that the question comes up as often as it does – I don’t know… Kazuo’s answer, in brief, is that there have been many films with stories about the kind of anomaly of brave slaves rebelling against an oppressive or immoral system, and he just isn’t as interested in telling that story as he was in the ways that we tend not to and the ways that we tend to accept our fates and the ways that we tend to lack the necessary wider perspective that would make that an option.”

When you reach the end of the book, you really do feel what Ishiguro was aiming for. But I found this even more interesting:

“When I have shown the film to Russian audiences the question doesn’t come up. When I show the film to Japanese audiences, in Tokyo, the question doesn’t come up. There are societies where the process of that society and the reality of the atmosphere of that society is so pervasive, since birth, that people are raised to believe that it’s noble to, be a cog, really, and fulfil your destiny and your responsibility to the greater society. It’s just how these characters think. It’s a very western idea and a very American idea that a movie story is somehow broken if it’s not about a character who fights.”

There it was: my Americanness, despite not being American at all. (Although, does Canadian count?) I am conditioned in the Joseph Campbell school of the hero’s journey — looking for the fight, the struggle for freedom, the escape from the system. Instead, these characters seem to find freedom through acceptance rather than through escape, which is, ultimately, how most of us live. The systems we both relish in and rail against are far too big for any one of us to meaningfully escape. Instead, we find our own ways of coping, succumbing to some version of the Serenity prayer in the quest to enjoy what precious little time we are allotted.

This really resonated with me becuz I've noticed how easy it is to ignore the hidden costs of comfort. The sweatshop comparison is spot-on about how we compartmentalize suffering to enjoy cheap goods without feeling guilty. I worked breifly in supply chain and saw firsthand how companies deliberately obscure the production conditions to maintain that psychological distance.