Should we say goodbye to GDP growth?

In Doughnut Economics, Kate Raworth questions the dogma of economic growth and proposes a tastier alternative

I’m now in my fifth year working in climate and sustainability, which is far too long to not have read Doughnut Economics until this Christmas. I wish I’d read this book years ago, because it gave words to concepts I’d been thinking and feeling but couldn’t clearly articulate.

Here’s the basic idea: for a long time now, economists have thought about growth and GDP as largely divorced from the natural world. This is a major flaw, because without the natural world, there is no GDP and there is certainly no growth. Yet the opposite does not hold: more growth does not equal a more abundant planet. All of us are aware of the destructive effects our current forms of capitalism are having on the environment. It can’t go on forever. Something has to give.

What do we do about it?

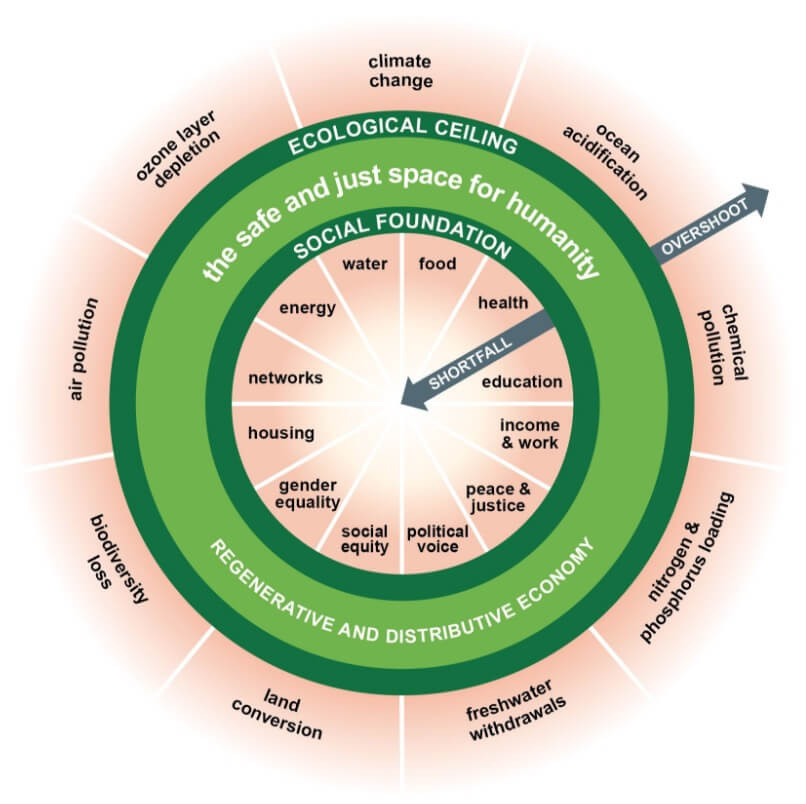

Instead of seeing economic growth as linear or exponential (as most optimistic economists do), this paradox of the natural world is the basis for Raworth, an economist and senior associate at Oxford University, putting visualizing economic prosperity inside a circle. (Environmentalists love circles!)

This is the doughnut in which Raworth proposes we exist: above the social foundation so as to give all humans the quality of life they deserve, and below the ecological ceiling so as not to push planetary boundaries to the breaking point. A delicate balance between human suffering and environmental suffering.

This might be obvious to everyone but me, but to anyone who finds this as confusing as I initially did, the idea is to live inside the ring of the doughnut — the literal dough — and avoid being in the empty middle (not enough) or the world outside the doughnut (too much). (The idea of staying ‘inside the doughnut’ led me to believe we were talking about the empty hole in the middle, but no — you want to literally be inside the dough.)

The crux of the problem: “No country has ever ended human deprivation without a growing economy. And no country has ever ended ecological degradation with one,” says Raworth.

How do we keep making people’s lives better, without ruining the planet?

The answer may lie in changing how we measure the former.

Is GDP growth always the answer?

Truthfully, we don’t fully understand GDP (gross domestic product). It’s a relatively new metric — Simon Kuznets invented it in the 1930s to put a value on the annual economic output of the U.S. Soon enough, the metric became the goal. Now that we could measure it, political leaders wanted to grow it.

The problem is that, although GDP gives us some idea of a country’s prosperity, it doesn’t tell anywhere close to the full story. Kuznets himself said so:

“Emphasising that national income captured only the market value of goods and services produced in an economy, he [Kuznets'] pointed out that it therefore excluded the enormous value of goods and services produced by and for households, and by society in the course of daily life. In addition, he recognised that it gave no indication of how income and consumption were actually distributed between households.”

Maybe we need to take GDP off its pedestal and start treating it like it is: just another tool in an economist’s or national leader’s toolbox. There are many problems that GDP does not measure, and many solutions that lie outside of increasing GDP. Raworth proposes we become GDP-agnostic:

“I mean agnostic in the sense of designing an economy that promotes human prosperity whether GDP is going up, down, or holding steady.”

A GDP that stands still may not be the quality-of-life disaster we imagine it to be. Here’s John Stuart Mill writing in 1848:

“A stationary condition of capital and population implies no stationary state of human improvement. There would be as much scope as ever for all kinds of mental culture, and moral and social progress; as much room for improving the art of living, and much more likelihood of it being improved, when minds ceased to be engrossed by the art of getting on.”

In the long term (and I mean long term), permanent GDP is just physically impossible. Take this explanation from What We Owe the Future, which I think about a lot:

“Suppose that future growth slows a little to just 2 percent per year. At such a rate, in ten thousand years the world economy would be 1086 times larger than it is today—that is, we would produce one hundred trillion trillion trillion trillion trillion trillion trillion times as much output as we do now. But there are less than 1067 atoms within ten thousand light years of Earth. So if current growth rates continued for just ten millennia more, there would have to be ten million trillion times as much output as our current world produces for every atom that we could, in principle, access.”

If permanent GDP growth is physically impossible anyway, maybe it’s time we started looking for other ways to increase prosperity for more people without continually trying to add zeroes to the net worths of the top 1%.

Even where GDP is high, problems abound

The real problem in most of the developed world today (and the world as a whole) is not a lack of growth (GDP is going up pretty reliably) but how that growth is distributed.

“It is national inequality, not national wealth, that most influences nations’ social welfare,” says Raworth, interpreting the conclusions reached by Richard Wilkinson and Kate Pickett in their 2009 book, The Spirit Level. “More unequal countries, they found, tend to have more teenage pregnancy, mental illness, drug use, obesity, prisoners, school dropouts, and community breakdown, along with lower life expectancy, lower status for women, and lower levels of trust.”

Sucks for poor people, right?

Yes — and everyone else. “The effects of inequality are not confined to the poor,” say Wilkinson and Pickett. “Inequality damages the social fabric of the whole society.”

Inequality jeapordises democracy, economic stability, and the natural world (by fueling “status competition and conspicuous consumption”). Conversely, equal societies, whether rich or poor, deliver healthier and happier populations.

What does a doughnut future look like?

Most world leaders don’t want to think about the doughnut. They’d rather think about the hockey stick, which may very well continue going up for the four or eight or whatever handful of years they remain in power. And how many leaders are truly focused on what happens after their terms?

Pushing the doughnut will be an uphill battle. Most of us experience a visceral reaction to hearing that GDP growth might not be the solution (I had it too). Instead of acknowledging just how much abundance exists today but is tied up in the wrong places, economists and governments are still pushing myths like trickle-down economics and ideas that equality follows growth in an effort to appease the handful of people at the top. Here’s the IMF in 2024:

“Despite evidence to the contrary, ‘the notion of tradeoff between redistribution and growth seems deeply embedded in policymakers’ consciousness.’”

Depressing.

Anyway.

Until old, disproven ideas are replaced with something more logical — until the doughnut and its sister ideas are household names — I’ll keep plugging away here on Substack.

This is great Amelia. I’m a member of the Wellbeing Economy Alliance, which is the perfect place to join the movement and has hubs in lots of places all over the world - weall.org.