Tech bros want us to think their tech is 'smarter' than us. They're wrong.

What's really at stake when we give our lives over to the tools that claim to know us.

How smart is it to trust ‘smart’ technologies?

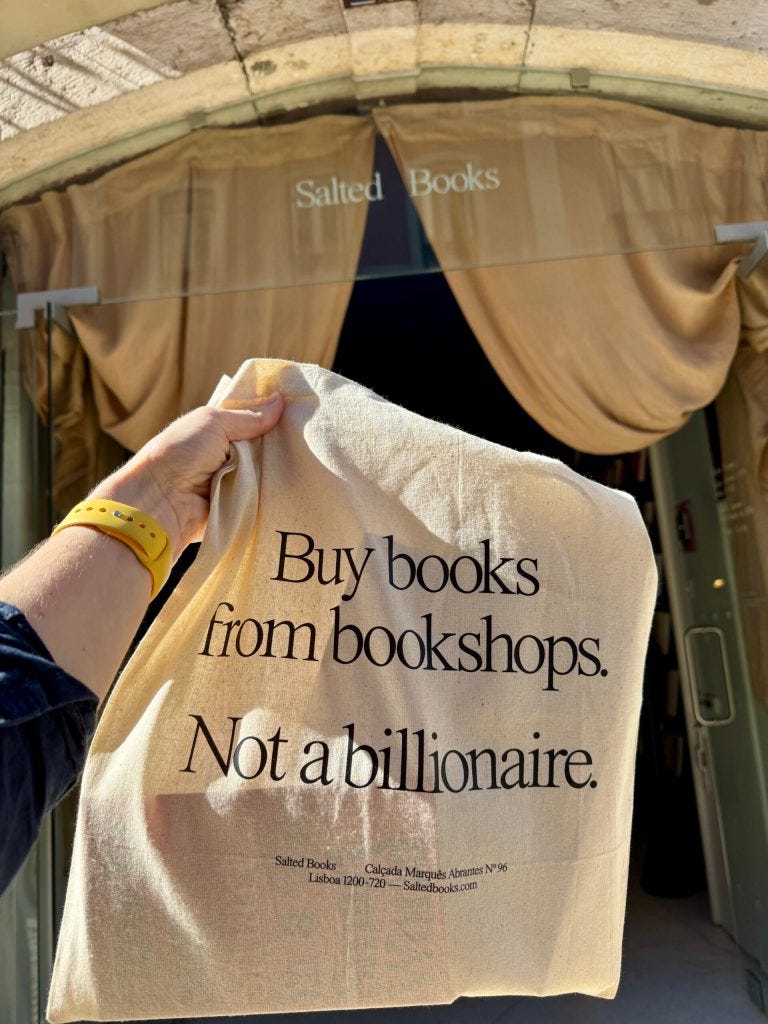

That’s the question at the heart of this book, which I picked up at Salted Books in Lisbon, Portugal (book-lovers, you will love Lisbon), where I also got this amazing tote bag. It was the first physical book I purchased in 2025, but in my typical fashion, I’ve only just read it.

I thought this book would be about keeping your attention span and critical faculties in the age of digital slop, but it turned out to be far more about the limitations of the technologies we think of as all-knowing and all-powerful. It doesn’t give strategies for guarding against tech-related cognitive decline in the way I thought it would, but it gave me something even better: an appreciation for the human experience.

Gigerenzer effectively asserts that the more we buy into the hype of AI and algorithms and big data and how ‘smart’ everything is, the more we lose faith in our own intelligence and ways of knowing and even our experience. At that point, he claims, “AI will tell us what to do, and [we believe] we should listen and follow.”

Rather than get down on ourselves for not being as fast or well-read as an AI, we must instead focus on the intelligence we do bring to bear. This may have nothing to do with ones and zeros and everything to do with how it feels to be a human being alive in the world from moment to moment. The author notes the impressiveness of computers that can beat humans at chess, albeit while consuming enormous amounts of energy and having to perform thousands of calculations at each turn. Humans, meanwhile, can play chess just using our brains (which only require a slice of pizza or two to power up). More importantly, we can have fun while doing it. Does much else matter?

The era of computers and big data has seen the brain regularly compared to a computer, and intelligence reduced to the ability to calculate. But Gigerenzer distinguishes between simple calculation — which is all computers can actually do — and the wide range of intelligence available to humans: judgment, intelligence, intuition — even courage.

We are trained to believe that ‘algorithms’ or AI can know far more than we can ever know, because of the complexity and opacity of their workings. In believing the hype, we put faith in this complexity and opacity, the author says, assuming it translates to intelligence. Yet neither is justification for ability.

Indeed, the author explores a wide range of scenarios (advertising algorithms, dating algorithms, criminal-identifying algorithms, etc.) where the supposedly all-knowing algorithms fail to perform in real-world conditions. What looks like a perfect profile match on a dating app can fizzle out in two minutes on a date, because the profile is not the person, and attraction is not a calculation. Humans have far more interesting, far more complicated ways of knowing — the way someone looks past you while speaking, the pitch of their voice, the smell of their cologne — than a computer can hope to understand.

We desperately need to understand the limits of these technologies — what they’re good at, and what they’re terrible at — to ensure we don’t trust them with decisions they aren’t capable of handling in real-world conditions.

This matters not just because we need to understand the dynamics at stake when we trade privacy for the sake of convenience or safety (read: surveillance), but because we need to know what we’re actually getting out of the bargain. If surveillance tech is no more effective at identifying criminals than old-fashioned policework is, or if an algorithm is no better at finding us love than the local bar is, why give up so much of our humanity — our privacy, our dignity, our humanity — for so little in return?

The author urges us to be wise not to the ways these powerful technologies take advantage of us, but the ways in which these technologies are simply not that powerful at all.

Facebook is said to know everything about you — but does it, really? It might know enough to sell ads to you, or help a surveillance state flag you, but does it know what it feels like to be you at 1 am on a winter’s morning, or under a tree on an autumn day? Does it know what it’s like to love you, to fight with you, to laugh with you? Of course not. But Facebook doesn’t want to know this — can’t know this. But in our obsession with optimising for what algorithms can know (putting more and more of our data online in exchange for ‘personalisation’ and convenience), we can’t lose the part of ourselves that these machines can never know.

Ultimately, this book might be less about staying ‘smart’ and more about staying human. — about remembering what it means to be human, and why it matters. Just because a machine can compute at a faster rate or ingest more data than we can, this does not make it better at making decisions for our lives.