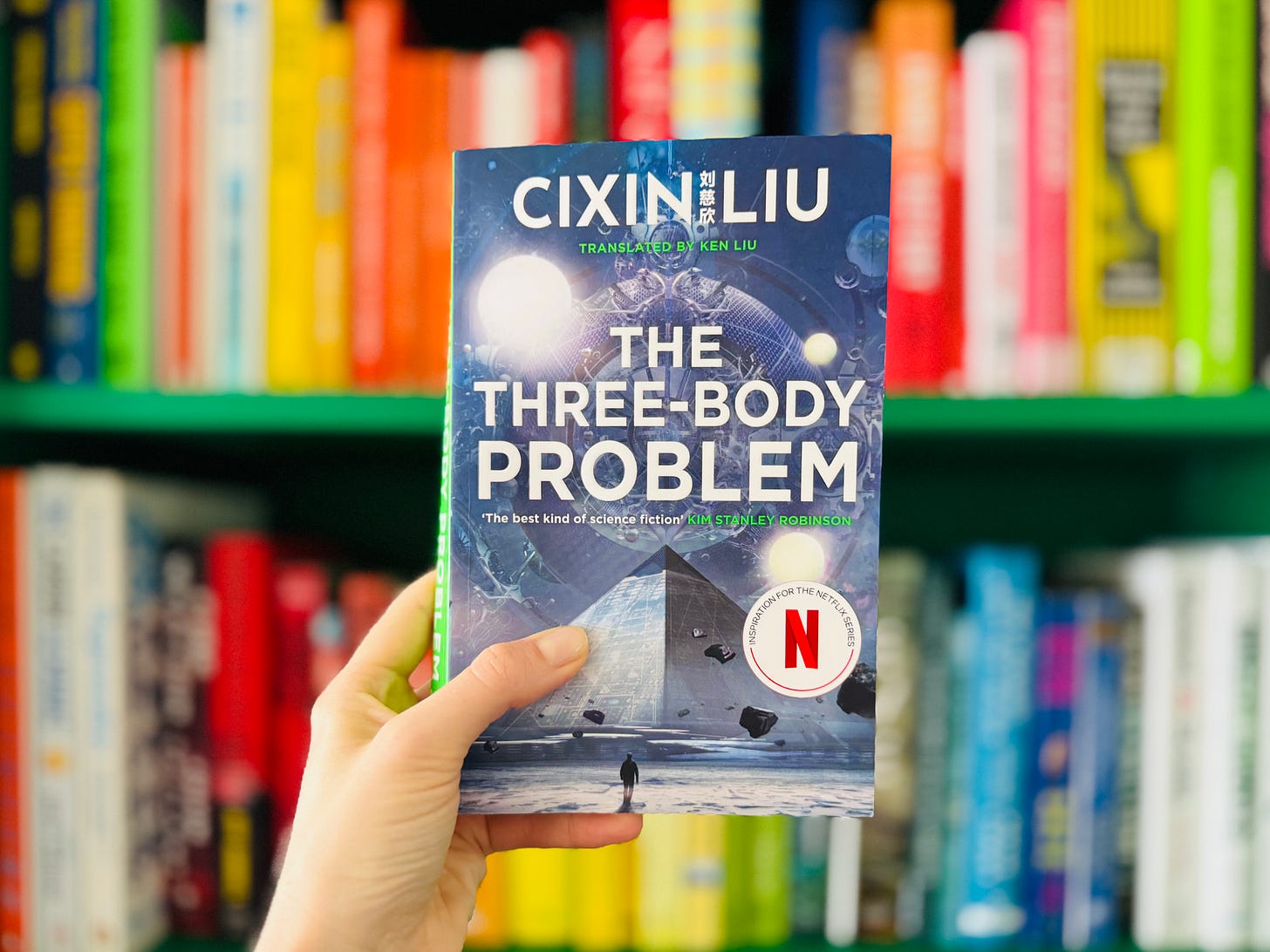

The Three-Body Problem, by Cixin Liu

A sci-fi novel for sci-fi people.

If you had told me even a month ago that I would spend a Friday night — and much of the next morning — in January reading a sci-fi novel written by a Chinese engineer, I would not have believed you.

But if you told me it had been recommended on the Ezra Klein show, well — now we’re talking.

That’s the story of how I ended up immersed in the world of The Three-Body Problem a few weekends ago, but let me back up a little. I barely read fiction, let alone science fiction (I’m working on improving the ratio). So I am not the target audience for this book, and perhaps that will show in my shallow interpretation, or my frustration at certain elements.

Overall: fascinating premise. Everything hinges on a good premise, and this one was enough to keep me engaged through some slower parts. I struggled with lack of any real characterisation or emotion from the characters, though I have to wonder how much of this is cultural or gender-specific or simply writer-specific. Given the premise, many of the characters faced unbelievable, life-altering moments, but these passed quickly with seemingly little reflection or depth.

The video game element to the plot was a little too much for me and seemed a little forced and unrealistic, but then, I have never played a video game in my life. Same goes for the scientific dialogue that seemed interminable at times. To someone with no background in physics, the way this stuff was dumped on the reader made certain sections a real slog. But perhaps, in the hands of the right reader, this stuff is enthralling.

People have asked me if I’m a character or a plot person, and I struggle to answer, because the truth is, I’m a sentence person. I can forgive a slow plot or cardboard characters if the words land in just the right way. In The Three-Body Problem I did find a few breathtakingly beautiful sentences — sparse, poetic, bold. But this language did not permeate the book in a way that it does in a book like The Handmaid’s Tale or A Place of Greater Safety (two recent fiction reads, look at me go).

Liu’s characterisations of the destruction of nature are profound, and I was feeling strong Rachel Carson vibes, leading me to laugh when the characters literally produce a copy of Silent Spring and it becomes a catalyst for the plot.

“The trunk was dragged away. Rocks and stumps in the ground broke the bark in more places, wounding the giant body further. In the spot where it once stood, the weight of the fallen tree being dragged left a deep channel in the layers of decomposing leaves that had accumulated over the years. Water quickly filled the ditch. The rotting leaves made the water appear crimson, like blood.”

What lands best from this book is its profiling of humanity — notably, the sense of alienation felt by humans on earth, and also by the creatures of the Trisolaris. Both civilisations (or rather, particular individuals within them) attempt to save the other at their own expense, convinced that goodness lies elsewhere. Liu seems to find humour here in the idea of aliens exploiting the ‘alienated’ to get them to turn on their own kind — not unlike what we are currently experiencing as our society divides and crumbles under the thumb of the tech bro aliens (anyone remember Zuckerberg in Congress?).

“Thus, we have reason to believe that there are many alienated forces within Earth civilization, and we must exploit such forces to the fullest.”

The warnings of division and senseless cruelty are hard to ignore, even though Liu claims not to be making any broader comment on humanity. We may be, as the aliens claim, simply bugs roaming the earth — but we could all be better bugs.