The offline origins of right-wing conspiracy theories

Will Sommer's 'Trust the Plan' suggests that the rise of conspiracy theories in the West has less to do with online algorithms and more to do with offline realities.

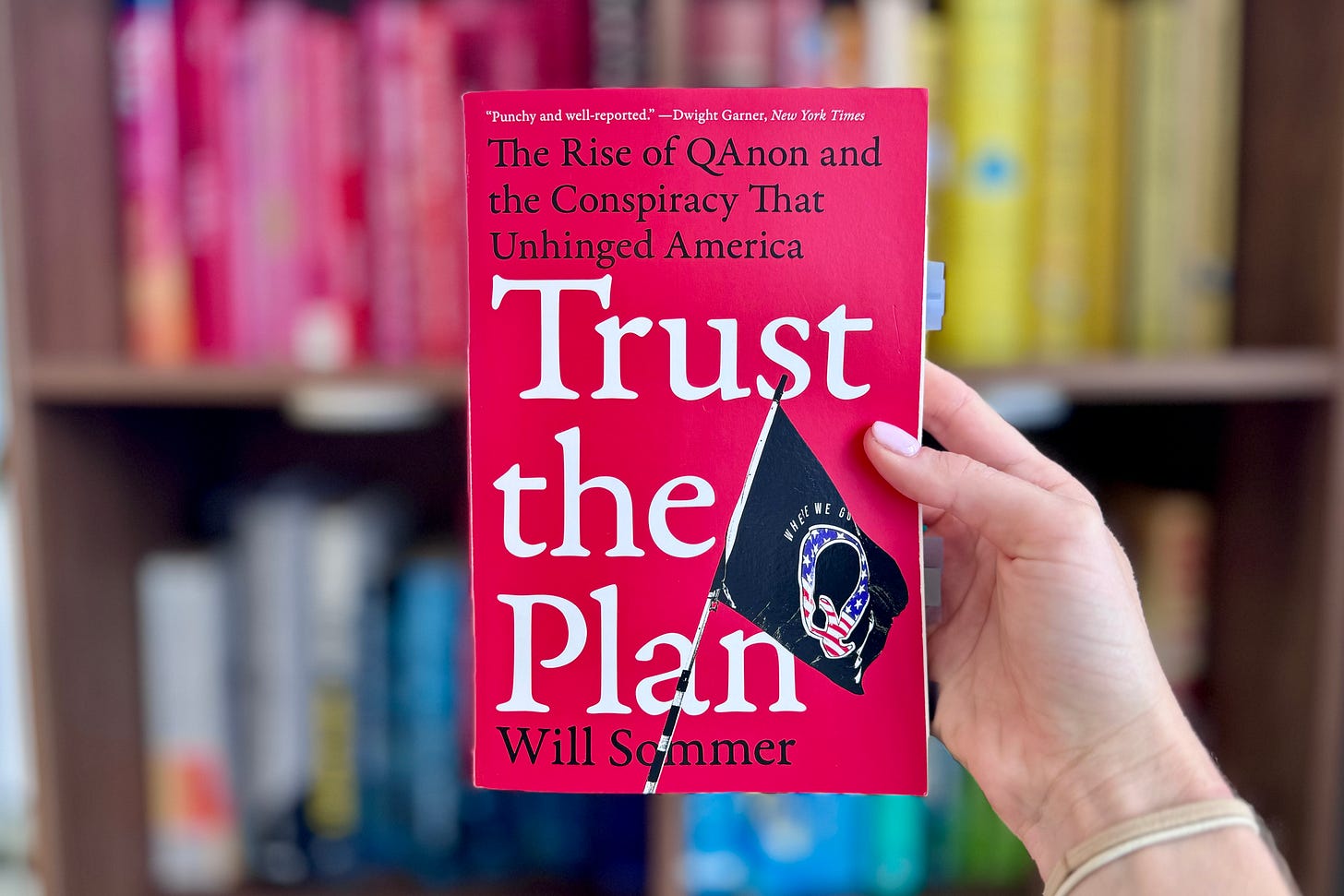

Author: Will Sommer

About: The rise of the QAnon conspiracy movement and what it says about the West

Obligatory stars: 3.75/5

Favourite quote: “Conspiracy theories have been a powerful force in American politics and culture since before the country’s founding, all the way back to the Salem Witch Trials.”

Main idea

QAnon’s story is unusual. How did such a fringe and extreme conspiracy theory manage to become accepted by so many people — including those in incredibly prominent positions? What drove such mainstream adoption of wild theories is not just social media algorithms gone wrong, but something more fundamental.

Summary and review

Much of the conversation on ‘fake news’ and conspiracy theories revolves around the users who fall prey to misinformation, the parties that concoct disinformation, and the algorithms that connect the two.

But Trust the Plan sheds light on the reality that conspiracy theories are the most attractive narratives is a world in which trust in mainstream institutions has been eroded — largely because people no longer believe these institutions actually care about them. Based on the inequality data available today, such a conclusion is hardly far-fetched.

Says Sommer: “I believe that anything that broadly improves conditions in the United States, from a universal daycare program to a minimum wage increase, would do more to keep people out of movements like QAnon than any kind of targeted anti-disinformation effort could.”

Mental models

Occam’s razor

The more I dive into the beliefs of QAnon and other conspiracies, the more I return to Occam’s razor (indeed, all of the razors). This is the principle that the simpler explanation — the one with the fewest moving parts or depending variables — is the more likely answer. The intricate web of QAnon beliefs is, quite obviously, not simple. (Although, as Sommer points out, perhaps part of the appeal of believing is having a relatively more “simple” narrative to explain everything that is wrong with the world.)

Probabilistic thinking

Closely linked to the razors is probabilistic thinking. Humans are notoriously bad at understanding base rates and estimating the likelihood of particular events. In the same way that we should rationally assess our chances of dying in a terrorist attack (less than those of being crushed by furniture, if that gives you any indication), so too should we at least attempt to rationally assess the probability that a secret cabal has managed to kidnap and torture children underground and that, of all people, Donald Trump has been chosen to save them. Is it impossible? Technically, no. But possibility in the real world is not binary; it exists on a spectrum of probability. We ignore probability at our peril.

Hanlon’s razor

I don’t know that we can apply Hanlon’s razor directly here, but let me at least try to stretch this into something coherent. Hanlon’s razor encourages us to “never attribute to malice that which is adequately explained by stupidity”. By extension, we might suggest that the world’s problems — though numerous — are far more likely due to carelessness or misplaced incentives (‘stupidity’, if you will) than outright malice. Politicians may have a lot to answer for, but it’s unlikely they are drinking the blood of children in underground D.C.

Did you read Trust the Plan? Let me know what you thought.

Relevant reads:

Facts and Other Lies: Welcome to the Disinformation Age (Ed Coper, 2023)

The Misinformation Age: How False Beliefs Spread (Cailin O’Coner & James Owen Weatherall, 2018)